The Tribes of Climate Change

By MATT SHAPIRO

This last week, I had a small conversation with Jason Emory Parker about climate change. I would say Emory is on “the left” and I’m on “the right” on this issue, but we both kind of felt that the arguments always seem to fall into a polarized debate and that it’s really hard to cut through that left-right divide. This made me want to try to think through why exactly that is.

The key points of the climate change position run something like this:

- Humans are expelling a huge amount of CO2 into the atmosphere

- High concentrations of CO2 make the planet warmer

- A warmer planet has all sorts of bad side effects, including but not limited to rising ocean levels

- We can arrest or reverse climate change through the political process (via regulations, taxes, other policies)

- We need to enact XYZ set of policies in order to arrest or reverse climate change

If you agree with all of these items, you’re probably on the “left” in terms of the politics of climate change. If you disagree anywhere along this line, you are probably on the “right.” These are not perfectly defined categories, but I find them helpful.

Climate Change Activism Is about Policy, Not Science

The problem with debating something like the Paris Agreement is that it sorts people into two buckets: the “climate change activists” and the “climate change deniers” (which is not a great term for reasons I explain below, but lets go with it for now).

One of the key lines from the activists is that the deniers are ignorant, anti-science or dishonest. If we’re being honest and looking at this group as a whole, this is not an entirely unfair charge. There is a lot of ignorance and rejection of fairly well established climate science within this group. But there are also many people who accept the science but reject the policies that climate change activists promote.

The thing about the actual science of climate change is that it is mostly about points 1, 2 and 3 as listed above. When people talk about the “97% of scientists” consensus on climate change, they’re talking about points 1 and 2. Nearly all scientists agree that the planet is getting warmer and humans are largely responsible for it in our generation of CO2.

Even though this is a pretty uncontroversial scientific position, there are a lot of people on the right who argue against this. Let’s not beat around the bush: These people are wrong. I’m not sure there is a way to argue them out of this unscientific position because, like almost everything else these days, it’s not really about facts, it’s about tribes.

But the twist to the story is that you can accept all the science and still be accepted on the right when it comes to climate change as long as you disagree with points 4 and 5. Similarly, you can be completely ignorant about the science on the left and still be accepted in the left’s tribe as long as you support the public policies that are touted as a solution to climate change.

Because ultimately this argument isn’t about science. It’s about policy.

Before we go on, let me state my position, for the record. For the science part of it, I basically subscribe to the IPCC report. This is a consensus report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on climate science. I use it is because I don’t want to get into arguments about why we should accept or reject the results of individual papers. There are lots of papers out there with lots of people claiming lots of things and in my experience, when an individual paper or study is highlighted (and thus shows up high in a Google search) it isn’t because it is particularly rigorous science, but because it aligns with what one of the tribes wants to hear.

So I stick to the IPCC, which is what Al Gore used when he talked about consensus in “An Inconvenient Truth.” Specifically because I’ve read the IPCC, I’m very skeptical about points 4 and 5. And for that reason, I end up on the right and people who couldn’t tell a statistical regression from a dinosaur call me anti-science.

What Is the Paris Agreement and Why Is It Important?

If we step back from our partisan battle-lines, I hope we can all admit that what matters on the left is not a firm grasp of science, but policy alignment. If you’re illiterate when it comes to actual scientific theory, but you accept liberal policy positions, you can yell “science!” all day long to the cheers of the crowd. If you accept all the science but think there isn’t that much that people can do to fix climate change, you’re on the “anti-science” side.

“Science” in the political debate surrounding climate change is often not science in the traditional sense but a tribal rallying cry to show that you are on the “good” side.

The Paris Agreement is a great example of this. According to Paris, the signed countries are committed to:

“Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change”

This is … an impressive and aggressive goal. Unfortunately, it is not one that is reinforced by any sort of plan. The targets submitted by the signatory countries will most likely result in “a median warming of 2.6-3.1 degrees Celsius.”

Not only is that nowhere near the target, but the target itself is, according to the IPCC report, basically a daydream.

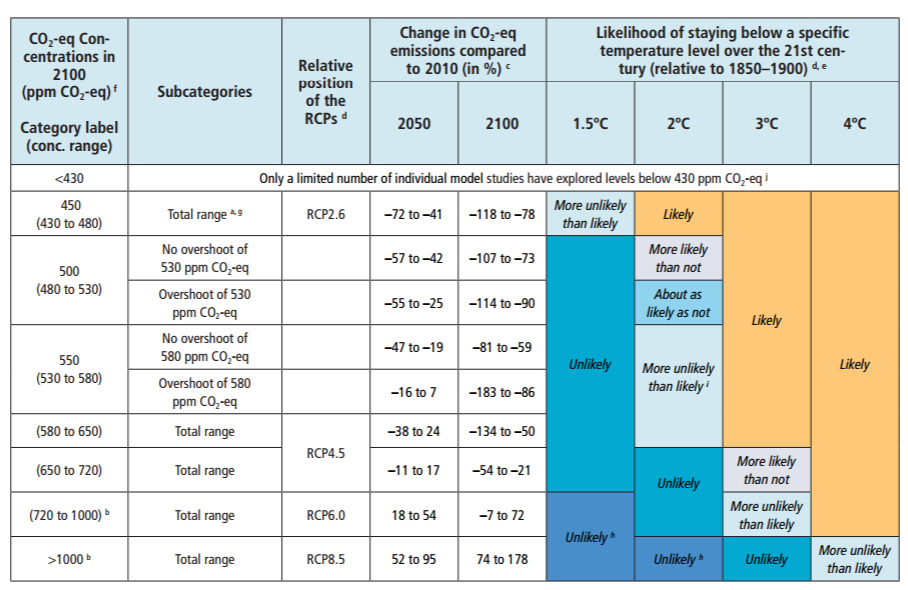

Only the best-case scenario from the IPCC, which has global emissions in the negative territory by 2100, makes “under 2 °C warming” likely. If we’re familiar with the science and also being honest, this is not a thing that is likely to happen. Based on the rate of CO2 entering the atmosphere, we could plausibly, with effort and determination, keep the CO2 concentration at about 550ppm, which puts us in the 2-3°C range.

450 ppm assumes humans emit negative emissions by 2100. This will not happen unless there are no more humans around.

That’s the science.

But many people still vow that the Paris Agreement will literallysave the planet.

I want to be both straightforward and kind here: I don’t fully understand why people think this. I look at the science and it seems pretty obvious. There is not a single climate model based on the targets submitted with the Paris Agreement that get us within spitting distance of the Paris goals.

My uncharitable side wants to say it’s little more than a tribal totem to rally around. Being a little more kind, maybe it’s a “shoot for the moon, even if you miss you’ll land among the stars” sort of attitude.

I asked Emory about this and he gave me this perspective:

“I see the climate story as something that’s progressed a lot over recent decades. I see Paris as a symbolic step towards making a difference. It matters a lot to get everyone on the record saying we’re all in agreement about doing something. That doesn’t mean it gets done, but it matters.

The US leaving will have little concrete meaning, but it has a lot of symbolic importance. ”

This aligns with Tom Nichols’ observation that having the US act like a global leader in this space is important if we actually want to be a global leader.

Tremendous damage to US leadership. Actual effect on anything, climate or jobs, is about zero. https://t.co/LqTMFt1UfL

— Tom Nichols (@RadioFreeTom) June 5, 2017

Which reinforces that a lot of climate change punditry is about politics, not science.

Does the Right Understand Climate Change?

Let’s not kid ourselves … the situation isn’t all that great on the right either.

There are three basic arguments against climate change on the right.

The first is the flat-out denial that it is happening. Denial that CO2 concentrations raise the global temperature, denial that humans are responsible for increased CO2 levels, denial that the global temperature is rising. I lean toward educated, cautious conservatism, and I can read scientific papers, so let me say in a plea to “my tribe”: these rejections of the essential components of climate change are distressingly common on “our team.”

Pointing to denials of essential climate science is also the stereotype the left would prefer to use for anyone on the right.

That stereotype gets harder with the second argument, which is that the climate change advocates are exaggerating the effects of climate change. This is … true-ish.

People who show images of water up to the entrance of the Jefferson Memorial might get a tens of thousands of retweets, but they’re not showing anything that the IPCC report predicts.

The absolute worst possible outer range of the worst case scenario has ocean levels up less than a meter by 2100, not “several feet” as Jason Samenow of the Washington Post claims. Exaggerations, hyperbole, and panic abound when talking about climate change, especially in the “pundit class” on the left. It’s almost as if there is a belief that making extreme claims will shock people into changing their minds.

But by focusing on these exaggerations from climate change advocates, we on the right tend to dance around actual bad things that are happening and are likely to happen. Things like coral reef depletion, which is devastating and actually happening. We focus on what people on the left get wrong. These distractions are easy to find as they, in their passion to impress upon us the severity of the situation, commonly accept wild exaggerations and very rarely call out their “own team” for getting the science wrong. These cases also let some of us on the right accuse the left of being anti-science because they often add in exaggerations and faulty reasoning that are not scientifically valid. But as we focus on these exaggerations, we push aside things that are genuinely concerning.

The third position we tend to take is to dismiss attempts to fix climate change. You can see some of that in my exposition on the left’s position. In this tactic, some on the right look at the situation, look at the “solutions” and say “that’s not going to do very much.” This is what Carly Fiorina said about climate change: It may be happening, but there is very little people can do to stop it. She was right about the science and right about the numbers, only to have people on the left savage her, call her stupid and a science denier. But she wasn’t wrong.

This position begs the question of what a responsible government should do about climate change and we on the right don’t have much of an answer for that … unless the answer is “very little.” I’m not saying “very little” is necessarily a bad answer. If you have a list of three expensive, ineffective policies and your fourth option is “do nothing,” then you may rationally choose option No. 4. But it looks as if we’re kind of punting on the problem because ultimately the tribal climate change battle lines don’t revolve around science or economics, but around “do something” vs “don’t do something.”

If you want the government to do something about climate change, you’re on the left. You could be wrong about the science, wrong about the predictions and process, you could exaggerate every effect and have no idea what is in the IPCC report, if you support the Paris Agreement and the idea that government needs to take the lead on this issue, you will be accepted on the left.

If you don’t want the government to do something, you’re on the right. Anywhere from blindingly ignorant disbelief in the basics of CO2 effects on the atmosphere to full acceptance of nearly every climate claim but solid in the belief that government is not the solution and the right will welcome you with open arms.

How Should We Then Live?

So what do we do with this? Can we come to any solution?

If you think the solution is the acceptance of the Paris Agreement along with its meager climate targets, a position that can only be reinforced by monolithic Democrat rule over the next 80 years, then the answer is no. If a single Republican (like Trump) bucking a climate agreement is all it takes to doom the planet, then we were always on the edge of the knife anyway and it was only a matter of time.

If you think the solution is a reduction in emissions through personal and industry commitment, then we might be able to talk.

“If a single Republican (like Trump) bucking a climate agreement is all it takes to doom the planet, then we were always on the edge of the knife anyway and it was only a matter of time.”

But we need to talk honestly. I tried to do that on Twitter and it was received in a relatively positive light. I suggested that groups that were most concerned about climate change should enter into a sort of gentleman’s agreement to severely reduce their travel and actively look for ways that our subgroups (tech industry, academics, professional class individuals) who are passionate about the threat of climate change can reduce our footprint.

Some used this as a “gotcha,” a sort of “if you were serious about this, you’d act like it” taunt, which is not at all what I intended. My Twitter thread was intended to say, “It’s clear we can’t rely on a stable government to do these sorts of things, so we should think hard about what we can do on our own.”

We also need to accept the very simple scientific fact that if we believe in climate change, we are in some ways past the point of no return. We’ve already made changes that cannot be reversed. There is no projected scenario, not even the best range of the best case IPCC scenario, in which the oceans stop rising. That’s a crappy reality to face if your message is “we need to do this thing (like the Paris Agreement) and we need to do it now. We can’t put it off four years or the world is doomed.”

But it’s a good reality if you know that every little bit counts.

We’ve already seen a bit of a drop in US emissions since they reached their high in 2006. Our GDP is up and we’re far more efficient per ton of CO2 emitted than we’ve ever been. There are reason to believe that the shift to a more digital lifestyle is contributing to this, but whatever the reasons, the truth is that we as a country have been doing much better on the climate front than many people give us credit for.

As a political issue, climate change is incredibly tribal. The disdain and hatred, the accusations and vitriol, rise to a wild point over this topic, and the battle lines have been drawn. I’m not optimistic they can be re-drawn within the next 10 years.

Which means that, if we think that emissions need to be reduced, we can’t rely on a government likely to change hands back and forth every few years to see it through. We need to make plans of our own. Let’s debate what those plans need to be.